Figure 1: Traffic Congestion Source: Dreamstine.com@Ruslan Sitarchuk

Figure

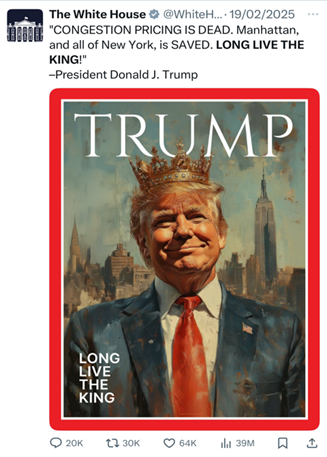

2: A Post From the Trump Administration Source: X@WhiteHouse

Have you ever been stuck in traffic, watching the minutes tick by while your frustration rises? You're not alone. The average commuter wastes 54 hours and over $1,000 annually in congestion! While London, Singapore, and Stockholm tackled this problem with congestion pricing, New York City's similar plan was abruptly halted in March 2024 by the Trump administration. Why was the plan terminated? Do these pricing schemes actually work? Let me show you how traffic jams reveal surprising lessons about economics.

Why Our Driving

Affects Others? Negative Side Effects

When you drive into a congested area, you're thinking

about your own costs – gas, time, maybe parking. What you're not considering

are the costs you're imposing on everyone else. Each additional car on a busy

road slows down traffic for everyone, creating what economists call a

"negative externality." This concept was first formalized by Arthur

Cecil Pigou back in 1920, but it perfectly explains our modern traffic woes.

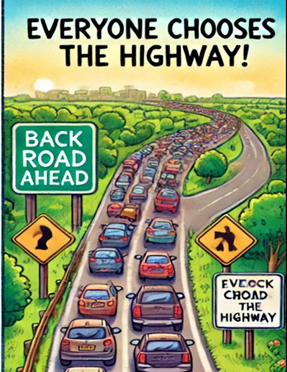

Figure 3: Two-Road Scenario Source: AI generated

Figure 4: Pigouvian environmental tax on negative externalities. Source: Nerudova, D., Dobranschi, M., & Adam, V. (2019). Can Pigouvian taxation internalize the social cost of platinum-group element emissions?

Imagine two routes between the same points – a highway

and a slower back road. Everybody naturally chooses the highway based on their

own benefit. But as more people make this choice, the highway gets congested,

eventually becoming slower than the alternative! This happens because we don't

pay for the delay we cause others when we join an already crowded road.

This externality creates a gap between the private cost that individuals consider and the true social cost of their actions. As shown in the diagram, without tax, we're stuck at inefficient point A where people overconsume because they ignore external costs. The tax fixes this by making consumers face true social costs, shifting us to optimal point B at quantity Q₁. The shaded triangle represents the eliminated inefficiency – economic gain from cutting wasteful consumption! The tax reduces congestion to an efficient level and maximizes overall welfare.

Why ‘Free’ Roads

Get Overused? The Commons Problem

Urban streets represent what economists call a "common resource" – something anybody can use (non-excludable) but where one person's usage reduces availability for others (rival). This classification explains why road networks inevitably face overuse and congestion without proper management.

As Frank Knight insightfully observed back in 1924, if roads were privately owned, owners would naturally charge more during peak periods to maximize value. Roads are mostly government-owned but unpriced, meaning costs remain chronically below their true value, leading to excess demand. This early insight connects traffic directly to what economists now call the "tragedy of the commons" – when a shared resource gets overused because no individual bears the full cost of their consumption.

During peak periods, this divergence becomes even more pronounced - think of roads like an all-you-can-eat buffet with no price difference between peak and off-peak hours. Of course, it gets overcrowded at dinner time! The result is wasted time, excessive pollution, and economic inefficiency that costs modern economies billions annually.

This example extends perfectly to busy urban centers where the problem intensifies dramatically. City centers experience the worst congestion precisely because they're valuable destinations where many people want to be simultaneously. Without proper pricing mechanisms, we create artificial scarcity through queuing rather than efficient allocation through market signals, turning potentially productive time into wasteful waiting.

Why We Keep

Choosing Busy Roads? Psychological Insights

People sometimes make irrational decisions—we keep

choosing routes that always seem to be congested. Behavioral economics reveals

several fascinating biases affecting our transportation choices.

Figure 5: Behavioral Economics is about our mind

At first, we hate changing routines: Most commuters never seriously reconsider their route or mode, even when alternatives would save time and money. This "status quo bias" keeps us stuck in inefficient patterns. Secondly, we don’t like risks: When considering a longer alternative route, we worry about the risk of spending more time way much more than time wasted on a shorter route's congestion which already equals or exceeds the time needed for the longer route. This "loss aversion" also makes us stuck in inefficient patterns. Hyperbolic discounting explains our persistent choice of congested roads because we irrationally overvalue the immediate gratification of taking a seemingly shorter or more familiar route while severely discounting the future pain of sitting in traffic that we'll experience just minutes later.

These cognitive biases explain why traffic solutions can't rely solely on rational economic incentives. Our decision-making is flawed in predictable ways, creating persistent inefficiencies in transportation networks. Policy solutions must account for these psychological quirks.

What Can Our City Council Do? Possible Solutions

Tax on congestion and pricing on using roads in busy areas are different routes but same destination. When cities implement congestion pricing, they transform roads from "common resources" into what economists call "club goods" – still limited in capacity but now with managed access.

The results from cities brave enough to try this

approach have been remarkable: London saw traffic drop 30% in the charging zone

with dramatically improved bus service; Singapore maintains free-flowing

traffic even during traditional peak hours; and Stockholm experienced a 14%

decrease in carbon emissions while significantly reducing commute times. These

success stories demonstrate how properly designed pricing mechanisms can

effectively balance demand with available capacity, creating more efficient and

sustainable urban transport systems that benefit residents through reduced

pollution, shorter travel times, and more reliable public transit

options.

Figure 6: The Congestion Charge Zone in London Source: Transport For London (tfl.gov.uk)

Figure 7: Average changes of traffic volumes for different types of roads on weekdays 6:00–19:00, April 2006 compared to April 2005. Source: Eliasson, J., Hultkrantz, L., Nerhagen, L., & Rosqvist, L. S. (2009). The Stockholm congestion-charging trial 2006: Overview of effects. Transport Policy, 16(5), 395-403.

The most sophisticated congestion pricing systems vary by time, location, and vehicle type, but implementation details are crucial. Successful approaches apply behavioral economics: positive framing reduces loss aversion (Kahneman and Tversky's prospect theory); trials overcome status quo bias; and visible revenue investments leverage the availability heuristic. Stockholm exemplifies this—opposition flipped from 70% against to 74% approval after experiencing benefits, demonstrating both preference reversal and Thaler and Sunstein's Nudge Theory principles. These behavioral insights explain why carefully designed implementations succeed where purely economic approaches might fail.

What We Have Got

Now? A Conclusion

Traffic isn't inevitable — it's the predictable result

of misaligned economic incentives. NYC's pause on congestion pricing ignores

decades of economic insight and global proof that it works. Cities worldwide

use smart pricing to cut congestion and boost mobility fairly and effectively.

Next time you're stuck in traffic, remember: it's not just traffic engineering,

it's about economics. Sometimes the best solution to a problem is putting the

right price on it.

Reference List

Eliasson, J., Hultkrantz, L., Nerhagen, L., & Rosqvist, L. S. (2009). The Stockholm congestion-charging trial 2006: Overview of effects. Transport Policy, 16(5), 395-403.

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243-1248.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

Knight, F. H. (1924). Some fallacies in the interpretation of social cost. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 38(4), 582-606.

Leape, J. (2006). The London congestion charge. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(4), 157-176.

Metcalfe, R., & Dolan, P. (2012). Behavioural economics and its implications for transport. Journal of Transport Geography, 24, 503-511.

Pigou, A. C. (1920). The Economics of Welfare. Macmillan and Company.

Transport for London. (2023). Congestion Charge

Impact Assessment. Retrieved from www.tfl.gov.uk/corporate/publications-and-reports

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.