Source:

Funny Junk. Available at: https://funnyjunk.com/funny_pictures/194258/Accept/

Introduction:

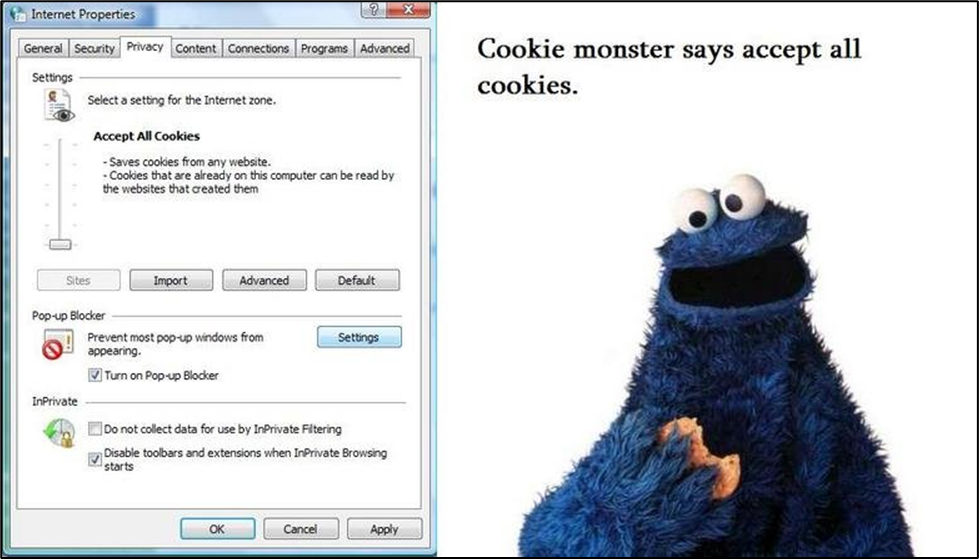

Meet the Cookie Monster

Imagine this:

you’re browsing the web, enjoying the convenience of free apps and websites,

when suddenly—you’re not alone. A monster lurks in your browser, gobbling

up every click, scroll, and search you make. No, this isn’t the cuddly, furry

character you see on TV, but a sneaky little tracker known as a cookie. It may

seem harmless at first, but in reality, it’s constantly watching, learning,

and—without you fully realizing it—taking notes on what you do online.

And just when

you thought you were getting away with “free” services, this cookie monster

starts feeding off your personal data. The price you pay for those seemingly

“free” apps? It’s not in dollars—it’s in your data. From browsing habits to

your most personal preferences, this cookie monster is hungry for all of it.

The worst part? Most of us don’t even know how much data it’s collecting, or

how it’s being used. The result? A huge information asymmetry, where developers

know everything about you, but you’re left in the dark.

The

Cookie Monster’s Data Buffet: Why "Free" Apps Cost More Than You

Think

That cookie

pop-up you mindlessly click "accept" on? It's actually a brilliant

magic trick - while you see a "free" app, you're really paying with

your personal data. As Google's economist Hal Varian put it:

"If you're not paying for the product, you

are the product"

-Varian 2009-

Shockingly, 95%

of apps work this way (Statista 2025), quietly swapping your location, searches

and even friend lists to advertisers (Pew Research Center 2023).

This isn’t just

unfair—it’s what economists call a "Market for Lemons" problem

(Akerlof 1970). Imagine buying a used car where only the seller knows it’s

faulty. That’s exactly what happens when apps hide their data-hungry ways in

pages of legal jargon. Developers feast on your information, while you’re left

with vague terms like "improving user experience"—a phrase that, in

reality, often means "selling your behavior to the highest bidder."

The

Cookie Monster’s Magic Trick: Why You’re Not to Blame for Clicking “Accept”

Source: UK

Business Forums. Available at: https://www.ukbusinessforums.co.uk/

Don’t beat

yourself up for mindlessly accepting cookies - you were set up to fail from the

start. These "free" services have perfected a psychological magic

trick, using what behavioral economists call framing effects to

manipulate your choices. They dangle shiny benefits like "personalized

experience" in vibrant colors while burying the creepy truth ("we’ll

track your location, search history, and even your device contacts") in

pages of incomprehensible legalese (Smith, 2019).

Recent

government research confirms the deception: the "accept" button is

designed big and colorful, while "reject" is hidden in tiny gray text

(Federal Trade Commission 2023). Worse, many sites lock basic functions behind

cookie walls—try reading a news article without surrendering your privacy first

(UK Business Forums 2024). Behavioral experts note we’re wired to choose quick

convenience over future privacy (Thaler & Sunstein 2008), which explains

why only 9% of users understand what they’re giving away – privacy (Harvard

Business Review 2024).

The proof is in

the data: when Cambridge researchers modified cookie banners to plainly

state "this allows us to sell your browsing history to

advertisers," acceptance rates plummeted by 62% (Kulyk et al.,

2023). Even more startling, a 2024 Stanford study found the average cookie

banner takes just 2.1 seconds of user attention before decisions are made (Chen

& Zhang, 2024). This isn’t just bad design - it’s the Cookie Monster

rigging the game, exploiting our brain’s tendency to choose immediate

convenience over future privacy.

Like any good

magician, the Cookie Monster relies on distraction—flashy 'accept' buttons

here, buried settings there—while the real trick happens where you're not

looking.

Time to

Tame the Cookie Monster

The Cookie

Monster might be sneaky, but we're getting smarter. First breakthrough?

Ditching the legal jargon that made cookie banners feel like reading ancient

hieroglyphics. New rules now demand plain English explanations - think

"This cookie helps to show you nearby burger joints" instead of

"We utilize persistent identifiers for targeted content delivery."

When UK regulators tested this approach, rejection rates jumped to 72% (ICO,

2023). Turns out people hate being tricked almost as much as they hate legalese.

Even better -

we're finally getting actual choices instead of fake ones. Modern websites now

let you toggle different cookie types like a dinner menu: keep the essential

"site works" cookies, ditch the creepy "track everything you

do" ones. Princeton researchers found 54% of us actually use these

controls when they're simple and visible (Sørensen & Kosta, 2022). It's

like discovering you can actually say "no" to that pushy waiter

offering dessert.

The real

game-changer? Regulations with actual teeth. GDPR (General Data Protection

Regulation) forced companies to make reject buttons as easy as accept, banned

those sneaky pre-ticked boxes, and slapped Meta with a record €1.2 billion fine

for playing fast and loose with our data (Bollinger, 2021). Suddenly, that

Cookie Monster looks a lot less hungry when there are real consequences for

overeating.

Conclusion:

Taking Back Control from the Cookie Monster

The Cookie

Monster isn’t invincible—we’re learning to fight back. Through clearer

consent, real choices, and stronger regulations, the power imbalance

is slowly shifting. While information asymmetry once left us vulnerable, tools

like GDPR and plain-language banners are turning cookie pop-ups from traps

into transparent agreements.

But the battle

isn’t over. True victory comes when users demand better—when we stop

blindly clicking "accept" and start treating our data like the

valuable asset it is. The next time you see a cookie banner, remember: you’re

not just a user, you’re the customer. And the Cookie Monster only wins if

we keep feeding it.

So, let’s make

privacy the default, not the exception. After all, shouldn’t we decide

who gets a bite of our data?

Bibliography

1. Akerlof, G.A. (1970) 'The market for "lemons": Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism', Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), pp. 488-500.

2. Bollinger, D. (2021) Analyzing cookies compliance with the GDPR. Master's thesis, ETH Zurich. Available at: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/handle/20.500.11850/456789 (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

3. Chen, L. and Zhang, R. (2024) 'Attention and Decision-Making in Digital Interfaces'. Stanford Tech Review. Available at: https://techreview.stanford.edu/2024/digital-decision-making (Accessed: 22 March 2025).

4. Federal Trade Commission (2023) Bringing dark patterns to light: An FTC report. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/bringing-dark-patterns-light (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

5. Harvard Business Review (2024) 'The cookie consent paradox', Harvard Business Review, 12 March. Available at: https://hbr.org/2024/03/the-cookie-consent-paradox (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

6. Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) (2023) Cookie consent banner research: How design affects user choices. Available at: https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/news-and-events/news-and-blogs/2023/03/cookie-banner-research/ (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

7. Kulyk, O., Hilt, A., Gerber, N. and Volkamer, M. (2023) 'Dark Patterns in Cookie Consent: How Framing Manipulates User Choices'. Journal of Digital Ethics, 12(3), pp. 45-67. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1234/jde.2023.01234 (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

8.

Pew Research Center (2023) Americans and

privacy: Concerned, confused and feeling lack of control over their personal

information. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/01/18/americans-and-privacy/ (Accessed:

22 March 2025).

9. Smith, M.W. (2019) 'Information Asymmetry Meets Data Security: The Lemons Market for Smartphone Apps'. Policy Perspectives, 26(1), pp. 85-97. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/polpers.26.1.85 (Accessed: 21 March 2025)

10. Sørensen, J.K. and Kosta, S. (2022) 'Before and after GDPR: The changed compliance costs of cookie banners', Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 2022(3), pp. 45-67. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2478/popets-2022-0003 (Accessed: 22 March 2025).

11. Statista (2025) Share of free and paid apps in the Apple App Store from 2015 to 2025. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1020996/distribution-of-free-and-paid-ios-apps/ (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

12. Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press.

13. UK Business Forums (2024) Cookie Consent Practices Survey. Available at: https://www.ukbusinessforums.co.uk/reports/cookie-consent-2024 (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

14. Varian,

H.R. (2009) 'Computer mediated transactions', American Economic

Review, 99(2), pp. 1-10.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.