Do you really know what terms you’re accepting when clicking ‘ACCEPT COOKIES’..?

The not so sweet truth about cookies

Internet browsing has become a necessity in the digital age. Without thinking twice, we scroll on social media, make online purchases and Google every question that comes to our minds. However, have you ever wondered how a pair of jeans you looked up once suddenly followed you for months? Remember that time you liked one TikTok of a child tripping over, and now your feed makes you seem like a sadistic child-hater? The answer lies in cookies – not the chocolate chip kind, but the digital trackers that follow your every move online. This is because we, like modern-day Hansel and Gretel, leave a trail of digital cookie crumbs behind with each click, visit and search.

Cookies are small text files, websites place on your device to remember information about you (Miyazaki, 2008). They track user behavior, remember login credentials, and recommend personalized content. Nevertheless, behind the scenes, they also hold power on a broader scale for data tracking, behavioural profiling, and price manipulation.

When presented with a cookie banner, most users click 'accept' because it is the most convenient and easy, which makes it a classic example of default bias. Companies leverage this predictable irrationality to maintain data collection practices despite nominal consumer choice.

Sounds scary. It kind of is.

Wait… what is asymmetric information?

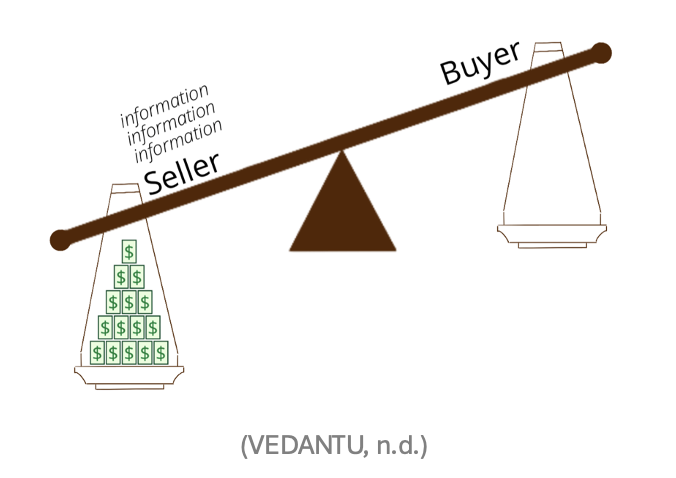

Let us break it down. Asymmetric information refers to economic transactions with an imbalance of information between the buyer and the seller (Bloomenthal, 2024). What does this actually mean? Let us look at an example by (Akerlof, 1970) in the used car market, where high-quality cars are described as 'peaches' whilst inferior cars are 'lemons'. Here, the party with more information about the vehicle being sold is the seller, and buyers don’t have adequate information to know whether they are being sold a peach or a lemon until after their purchase. Since consumers cannot differentiate between the qualities of the cars, adverse selection occurs. There is only one market price for all used cars, which is below the minimum price ‘peach’ sellers are willing to sell their cars at. This means the good stuff (peaches) leaves the market (Eeckhoudt et al., 2005) as no one wants to sell high-quality cars for the same price as low-quality cars.

This same logic applies to us… except now, the information imbalance is not about cars; it's about your data.

Cookies: tiny files, BIG power

Cookies track user information and behaviour, recording information such as their age, gender, address, and account numbers, to their movement between webpages, and how many times a particular ad appears while they’re online (Martin, Wu, and Alsaid, 2003). This tracking of internet users’ behaviour allows companies and third parties to create user profiles, allowing them to target ads, content, and products to specific consumers (Wadhwa, 2017).

Why? So, companies can target you with ads, products, and content they think you will click on. However, here’s the catch: while firms know a lot about you, you know nothing about what they know. Most people do not even understand what a cookie is, let alone how they are used (Hoofnagle, 2005).

And, yes, cookies do affect your wallet. Have you ever noticed that some things you see on Amazon are more expensive than the same things on someone else’s Amazon? Researchers

discovered that Amazon uses information about users’ browsing history, collected using cookies, to price the same products differently for different consumers. Those shopping for products after visiting different e-commerce websites were shown higher prices than those who only visited Amazon (Hannak et al., 2017). Even holiday websites get sneaky; the Wall Street Journal found that Orbitz, a travel booking company, used cookies to differentiate between PC and Mac users. Knowing that Mac users spent up to 30% more on hotel bookings than PC users, they displayed more expensive hotel options to Mac users (Huspeni, 2012). This represents the economic price discrimination theory, where companies practice charging different prices to different consumers for the same product.

The Negative Externalities: The Pollution of Privacy

Think of cookies as digital pollution. You are minding your own business and looking up a recipe for ice-cream, but your data is being scooped up and passed around. As economists call it, this creates a negative externality where the cost is put on third parties not involved in the transaction. In this case, the transaction is between the websites that collect and sell your data and the firms that use the data. And guess what? You are the third party! You do not know how your personal information is used, but you must deal with the negative consequences of losing your privacy and manipulating your online experience (Wehkamp, 2022).

Bibliography:

Akerlof, G.A. (1970). The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, [online] 84(3), pp.488–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431.

Bloomenthal, A. (2024). Asymmetric Information in Economics Explained. [online] Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/asymmetricinformation.asp.

Eeckhoudt, L., Gollier, C. and Schlesinger, H. (2005). Economic and Financial Decisions under Risk. HAL (Le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe). doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400829217.

Hannak, A., Soeller, G., Lazer, D., Mislove, A. and Wilson, C. (2017). Hannak, A., Soeller, G., Lazer, D., Mislove, A. and Wilson, C. (2014) Measuring Price Discrimination and Steering on E-Commerce Web Sites. Proceedings of the Conference on Internet Measurement Conference, Vancouver, 5-7 November 2014, 305-318. - References - Scientific Research Publishing. [online] Scirp.org. Available at: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2066911 [Accessed 2 Apr. 2025].

Hoofnagle, C.J., 2005. Privacy self-regulation: A decade of disappointment. [online] Electronic Privacy Information Center. Available at: http://www.epic.org/reports/decadedisappoint.pdf

Huspeni, A. (2012). Orbitz Tries To Charge Mac Users More. [online] Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/orbitz-tries-to-charge-mac-users-more-2012-6.

Martin, D., Wu, H. and Alsaid, A. (2003). Hidden surveillance by Web sites. Communications of the ACM, 46(12), pp.258–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/953460.953509.

Miyazaki, A.D. (2008). Online Privacy and the Disclosure of Cookie Use: Effects on Consumer Trust and Anticipated Patronage. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, [online] 27(1), pp.19–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.27.1.19.

Wehkamp, N. (2022). Internalization of Privacy Externalities through Negotiation. Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3487553.3524631.

Wadhwa, V. (2017). Leading Edge: Regaining Control Over Personal Data. ASEE Prism, 27(3), 21-22. doi:https://www.jstor.org/stable/26819919.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.